Toby Doyle

Toby Doyle, Community Cricket National Coach Development Manager, has played a key role in changing the way community coaches in New Zealand are prepared for their role. This includes receiving frequent personalised guidance from coach developers in real-world settings.

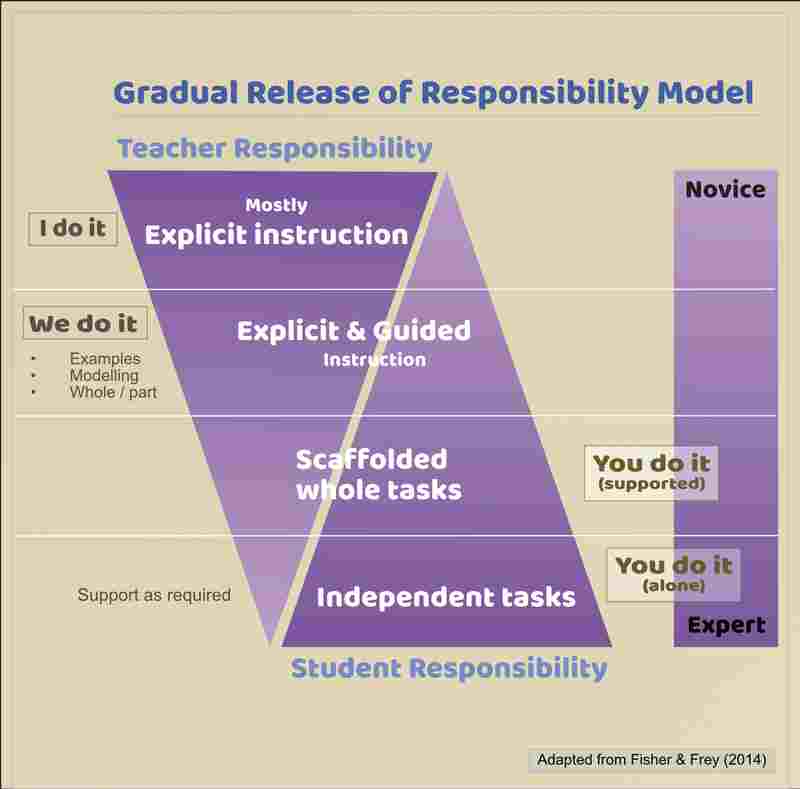

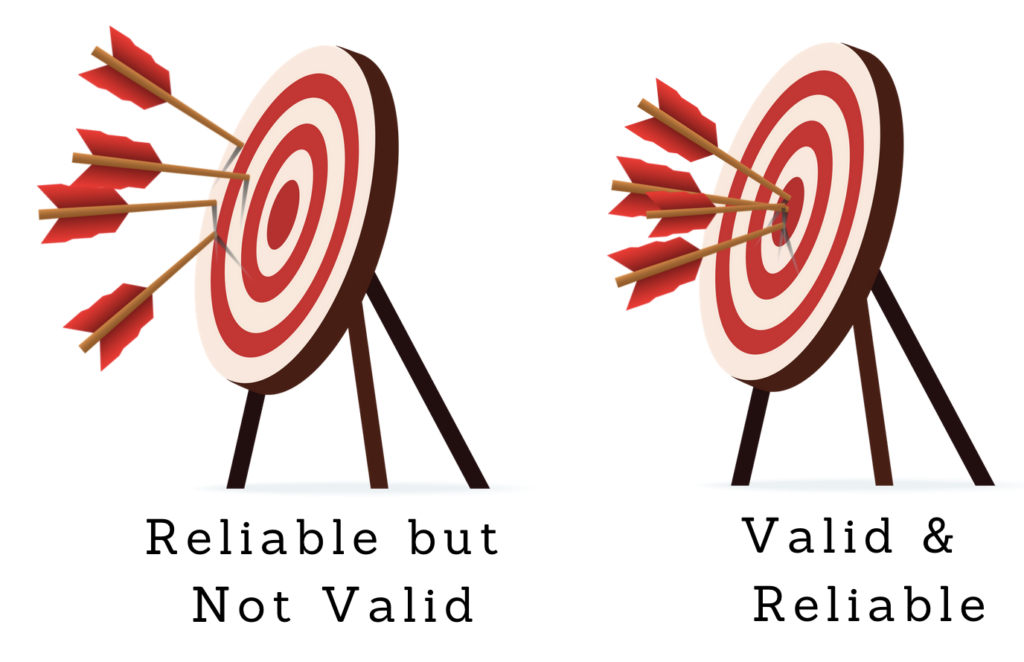

In this approach mastery is favoured over covering the curriculum. Observation, guidance, and support replace critique and ticking off a skills list. The learning coach’s context and their individual needs shape the support offered.

The NZ Cricket model of learning and development has been well received by coaches, the majority of whom have little interest in accreditation or being assessed. Quality is assured by the high level of personalised support that is afforded each coach.

Toby Doyle’s current role is the Community Cricket National Coach Development Manager at New Zealand Cricket. His path has included playing, coaching, developing coaches, and even training other coach developers.

Toby is deeply passionate about enabling quality coaching in community sports. His learning journey reflects a non-linear path, driven by a commitment and reflection to continuous improvement. Beyond his professional life, Toby is a father of three young children, and his fiancée, Hannah, shares his passion for coaching and sport. With his cricket playing days behind him, Toby now finds joy in playing the odd game of golf.

Toby has been fortunate to participate in the International Cricket Council’s Master Educator Program and has served as a trainer in the latest iteration of Sport New Zealand’s Coaching For Impact program.

How did you get into the Coach Development role?

I transitioned into a Coach Development (CD) role from my previous position as a Development Manager at Canterbury Country Cricket Association (which I was in for 7 years). This role required me to deliver key coach development initiatives for New Zealand Cricket, which involved engaging with the community to facilitate learning and support for community coaches.

CD philosophy

Empower individuals to become the best versions of themselves through a holistic and strength-based approach.

Best parts about the role

As the Community Coach Development Manager with New Zealand Cricket, I have the opportunity to nurture the potential in others—both coaches and coach developers. I am constantly seeking ways to improve and refine our coach development system and processes within New Zealand cricket.

Support for coaches

My work focuses on three key domains: the NZC Coach Learning System, the NZC Coach Developer Network, and Women in Coaching within Cricket.

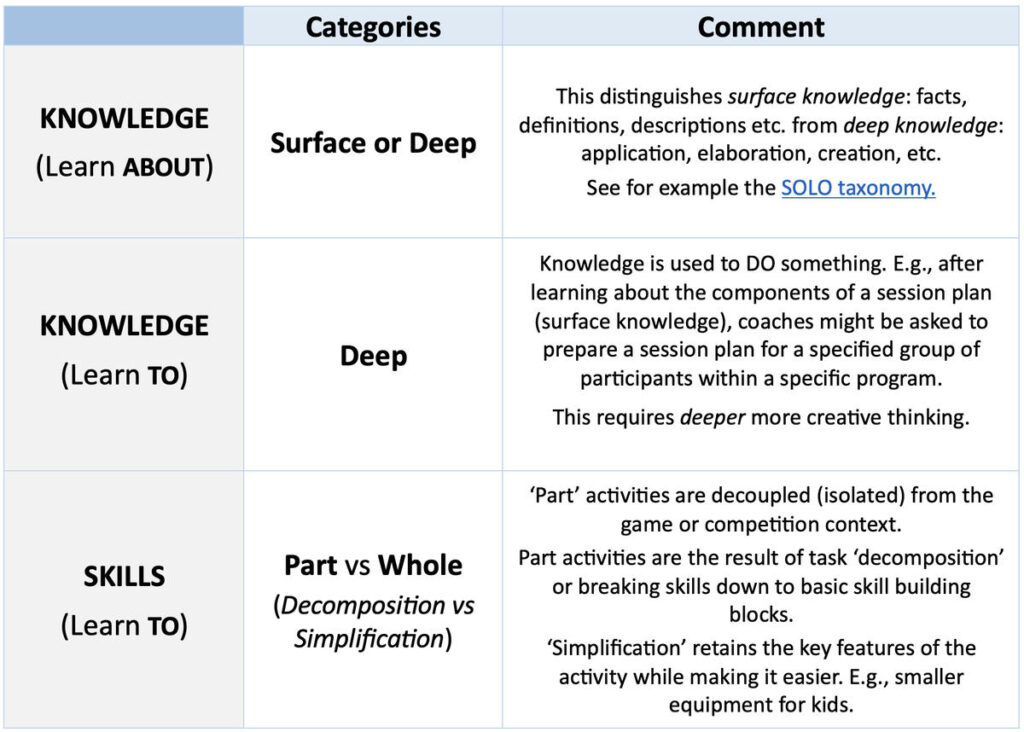

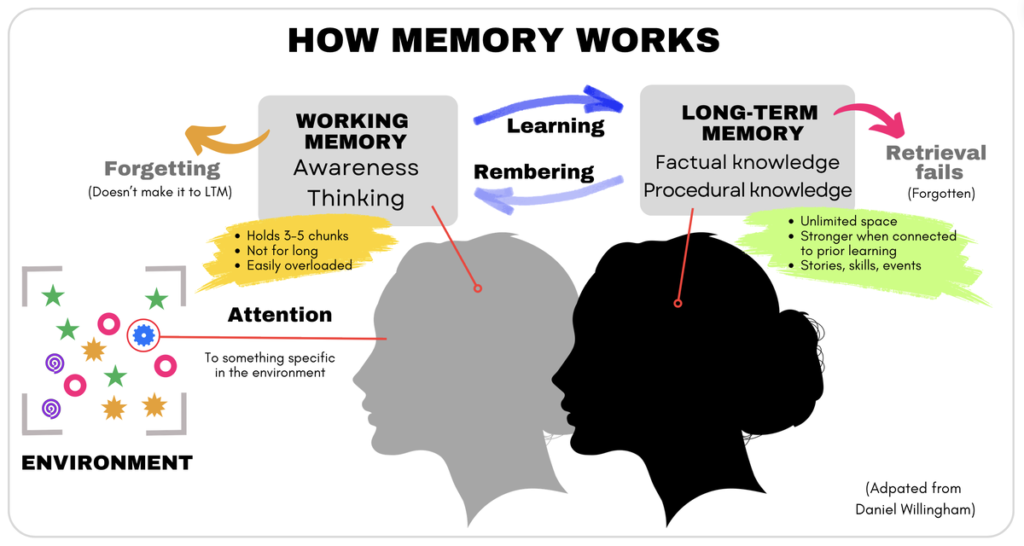

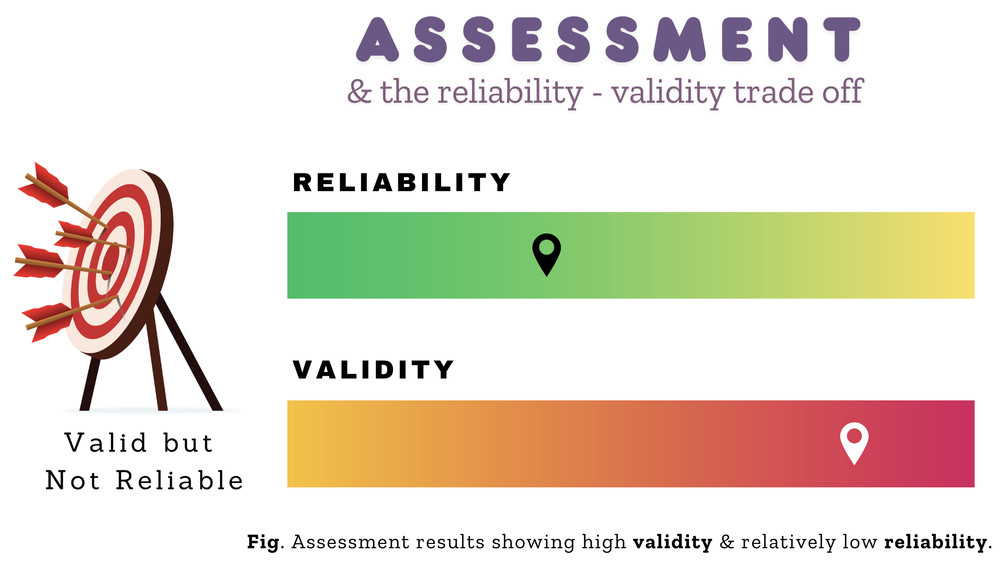

- Coach Learning System: Over the past decade, the NZC Coach Learning System has evolved from a linear, assessment-driven model to a modular system focused on ‘just in time’ learning. This shift recognizes that most of our coaching population consists of volunteer parents who seek practical information rather than formal qualifications.

- Coach Developer Network: We currently have 90 active coach developers supporting approximately 3,000 coaches. My role involves providing leadership, mentorship, and ongoing professional development for these coach developers. This includes facilitating communities of practice and guiding them through a rigorous plan-do-review process centred around their regional coach development plans.

- Women in Coaching: With 13% of our registered coaches being female, increasing this percentage is a major focus for New Zealand Cricket. We are working to create inclusive and safe spaces for female coaches at the grassroots level. Additionally, we offer a centralized program called ‘Pathway to Performance’ to equip aspiring female coaches with the skills, tools, and knowledge needed to advance in their coaching careers.

If I had more resources

I would place a coach developer in every club and secondary school across New Zealand.

Additionally, I would develop an AI-driven coaching app to provide individualized support to coaches in real-time.

Do you work in partnership with other coach developers?

Yes, I collaborate extensively with coach development leaders from other sports both within New Zealand and internationally. Currently, we are partnering with New Zealand Hockey to deliver a trainer program aimed at developing coach developer trainers.

My role as a Master Educator with the International Cricket Council has also allowed me to build valuable networks with global coach development leaders.

Recently, I have been involved as a trainer/facilitator in the Sport New Zealand Coaching for Impact program, which is designed to develop youth and secondary school coaches. I have also assisted New Zealand Rugby in facilitating a World Rugby Educator course to develop new coach developers in a rugby context.

Highlights and challenges

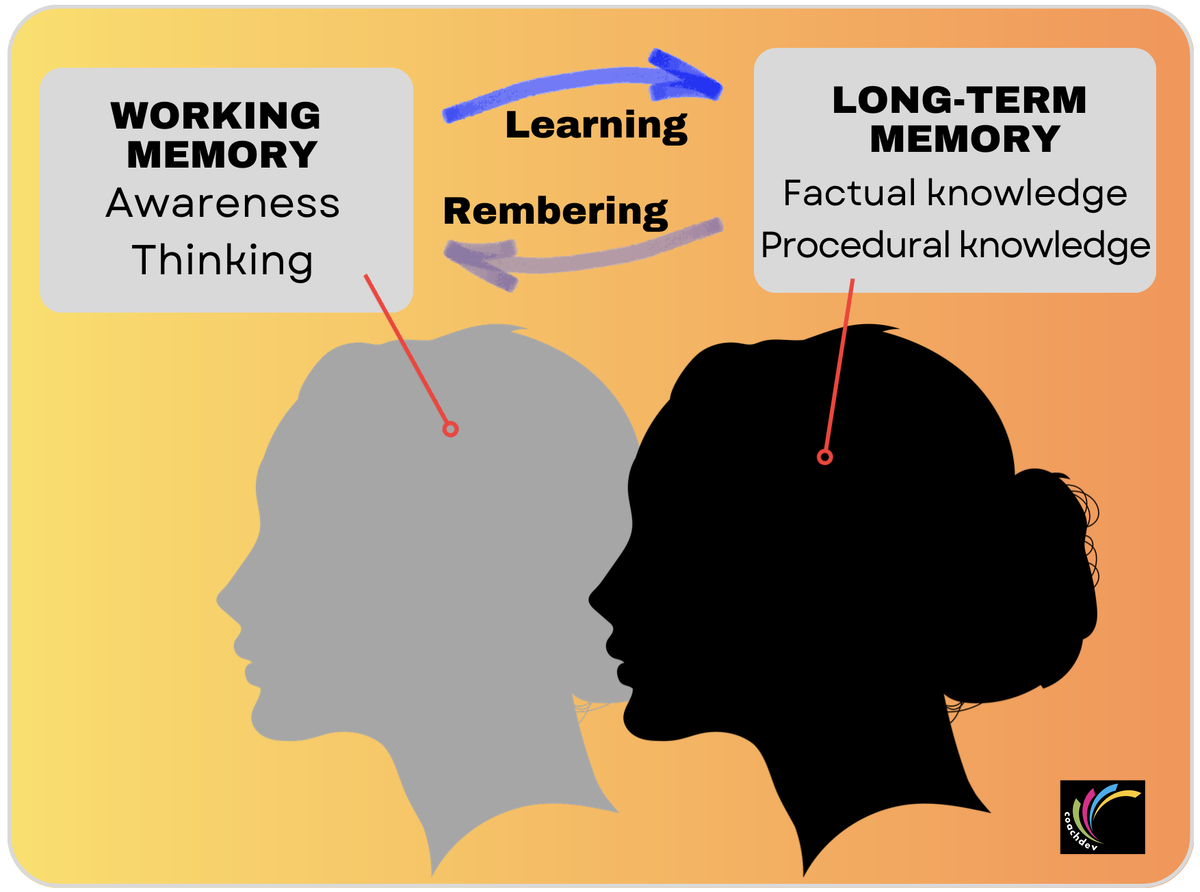

The most rewarding aspect of my role is seeing others thrive and grow. I learn a great deal from observing other coaches, coach developers, and trainers in action. Being part of the recent adaptations to our learning system, aligning it with 21st-century andragogy principles, has been a significant achievement.

A continual challenge is effectively communicating the impact of coach development work to decision-makers, ensuring they recognize its importance.

“The most rewarding aspect of my role is seeing others thrive and grow.

Do you have a mentor?

Yes, I have a mentor who helps me continue to learn, reflect, and grow in my leadership role.

TOP 4 COACH DEVELOPER TIPS

- Discover the coach’s motivation or ‘why’ and link any learning and development back to this

- Be your authentic self — skilfully

- Focus on strengths rather than gaps

- Reflection is the secret sauce to learning