Part 1 - Reimagining assessment and course delivery

What if we expanded our view of assessment? What if assessment and learning were intermingled so that the two were indistinguishable? In this view, assessment IS learning and learning IS assessment.

Imagine coach learning and development where CD observations of coaches in action, followed by supportive conversations, were part and parcel of the learning process. From time-to-time peers would be part of the conversation too, and coaches would learn and use the skills of review and reflection.

Imagine too, that this change in approach provided an alternative to traditional assessment.

This view of coach learning and development requires a mindset change in the way we go about preparing coaches. Particularly in accreditation / certification courses. Is a different mental model of what coach development and assessment looks like required? And would it have its own set of challenges to address?

Toby Doyle from New Zealand Cricket has been leading the charge encapsulated in the latest iteration of the NZ Cricket Coaching System with a range of initiatives, some of which are discussed below.

In England, Liam McCarthy at Leeds Beckett University has done much work on rethinking assessment in coach development (1). His propositions have added weight as they are grounded in his collaborations with major sporting organisations. His work is described in a recent book of perspectives on assessment and development from around the world (2).

ASSESSMENT & LEARNING INTERMINGLED

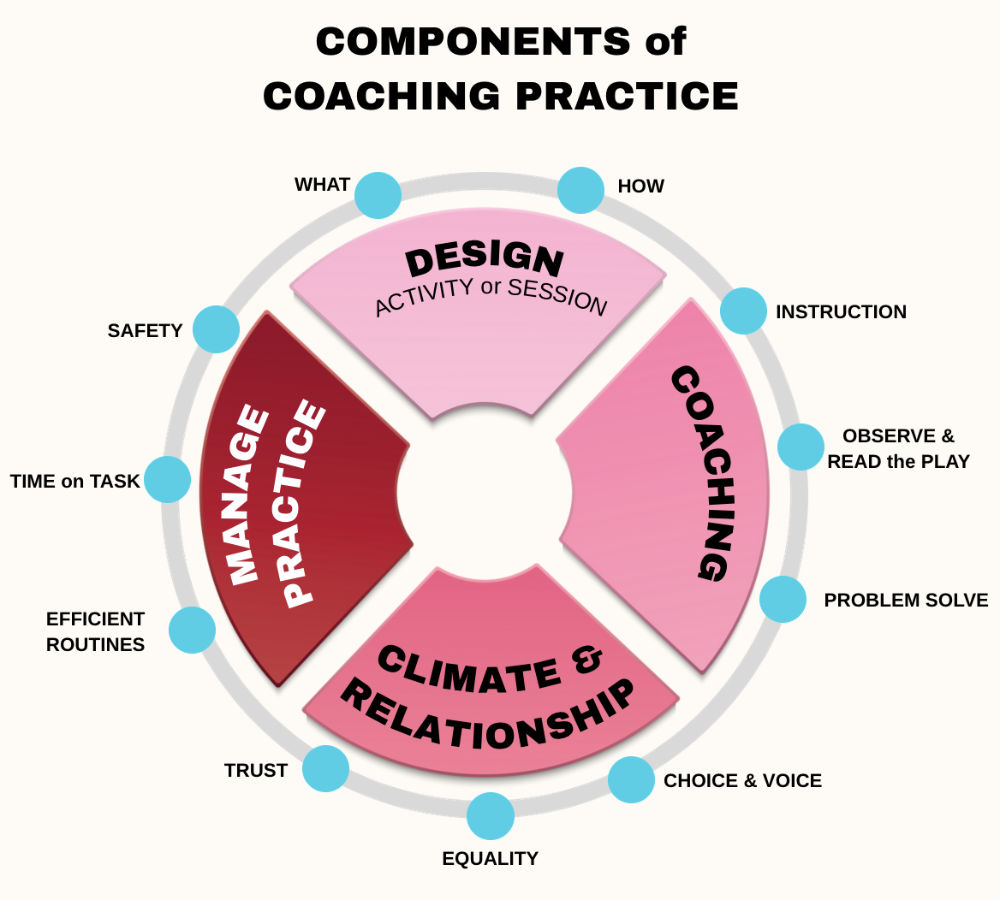

A personalised coaching experience approach is dependent on courses paying far more attention to the HOW of coaching. That is putting COACHING PRACTICE front and centre. See an earlier article in coachdev by the pioneer coach educator Eric Worthington here.

COACHING PRACTICE

‘Coaching practice’ is just that – a coach applies their knowledge to a simulated or real-world coaching task.

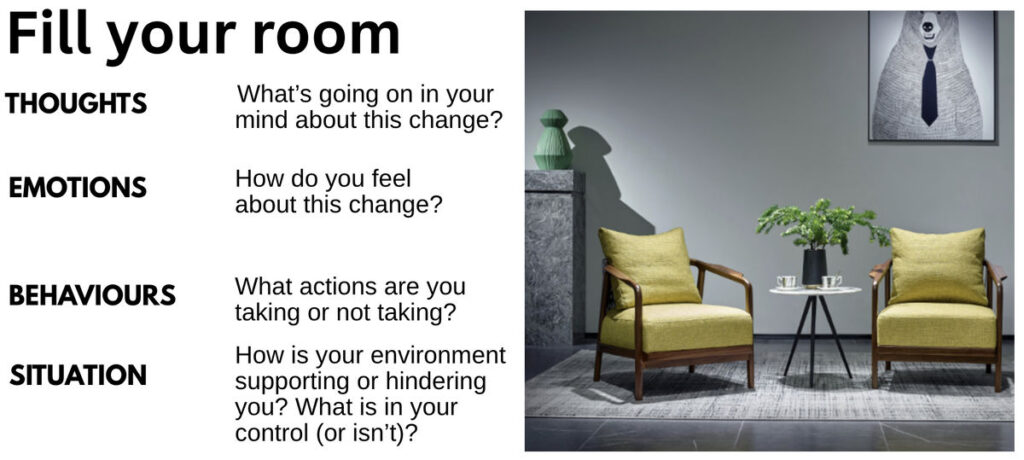

Coaching involves finding the best combination of a developmentally favourable coaching environment, the task at hand and the athlete’s needs. While remembering all along that coaching is both a technical and relational challenge. The coach’s teaching skills are the magic that brings it all together.

The graphic opposite is an attempt to capture the essence of a coaches role when guiding coaching experience sessions. (This model is expanded in Part 2).

AN ALTERNATIVE MODEL: KEY FEATURES in BRIEF

A key feature is the increased time and emphasis on the HOW of coaching through coaching practice.

- It starts with course DESIGN. Plan for a major part of the coaches’ learning taking place on-the-job. This should be guided by a trained CD. If that is difficult, ramp up the amount of time (> 50%) spent on micro-coaching activities within the F2F course. Sufficient time should be allocated to discussion and debrief / reflection.

- CONTEXT is important, so some guided coaching in the coach’s club or organisation is of great value.

- The DISTRIBUTION of the LEARNING OVER TIME is just as important (maybe more so) than learning in a single block of time (3).

- Ensure there is sufficient time for coaching practice with a strong emphasis on the HOW of coaching – organising, reading the play, and adapting instruction. As confidence grows coaches sharpen their own learn-to-learn skills including reflection and self-regulation. See Kirsi Hämaläinen’s Top 4 CD Tips here (Point #1).

THE SKILLS to be LEARNED DETERMINE the ‘THEORY’ to be COVERED

- COACHING KNOWLEDGE is important, but it needs to be in the right proportion, delivered in the most efficient means and reinforced in hands-on settings. Theory teaching in many courses does not pass this test of application to a real-coaching situation. The answer is not to allocate more time to theory.

- ONLINE LEARNING is an efficient way to deliver the ‘theory’. It should contain a mix of surface and deep knowledge challenges, and preferably use FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT methods to deepen learning and ensure some quality control.

FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT

The aim of formative assessment is to provide both the learner and CD with feedback about progress and next steps in the learning. Formative assessments are low stakes activities that are integral to the learning.

- Other TECHNOLOGY ASSISTED LEARNING methods can complement the online learning or for some topics, replace it. Webinars that are discussion based (and not lectures) can be helpful.

- Too much ‘theory’ is worse than not enough. Emphasise NEED to KNOW stuff over NICE to KNOW stuff. Use the simple test: Will the coach be able to see the connection between the theory and their practice AND use it?

REQUIREMENTS for the ALTERNATIVE APPROACH

Listed below are essential ingredients for a successful personalised coaching experience approach that will stand up to scrutiny:

- Multiple coaching experience sessions separated in time are required to facilitate real learning and for the CD to make judgements about capability.

- Formal club or organisation support in practice guided by a trained coach educator / mentor further enhances the quality of the experience and can be an integral part of accreditation / certification programs (Access the Australian Sports Commission Supporting Coaches in Practice course here).

- Well-structured partner and group work (4) that provides opportunities for peer-to-peer teaching and social learning can have a significant positive impact on learning. (5)

- The CD / coach educator / mentor should be trained in the skills required to guide growth-related conversations that flow out of in situ learning. (For more information, see here.)

- Appropriate CD / coach records of achievement should be kept. This process should be as low key as possible with the emphasis on GROWTH and not ASSESSMENT.

- Coaches should become increasingly proficient at being able to articulate the task at hand, its purpose, ‘what good looks like’, and be able to reflect on their own thoughts, feelings and behaviours flowing out of the coaching experience challenges.

- The personalised coaching experience approach demands a shift in time allocated to hands-on coaching (micro-coaching or supported practice).

- It is important that essential (need to know to coach) ‘theory’ is provided through well designed technology assisted learning (e.g., online learning, webinars, etc). This may mean a reduction in time given to non-experiential learning.

- The most powerful way to deepen knowledge is to do something with it. That is to apply it in practice. CDs have an important role in making the links to practice.

HOW WILL WE KNOW if the COACH is CAPABLE?

The personalised coaching experience approach described here has to stand up to scrutiny. Is it contributing to the development of ‘job-ready’ coaches?

By the way, much of what passes for ‘rigorous’ assessment doesn’t do all that good a job of assessing coaches’ coaching capability anyway! Something that has been described as the ‘illusion of competency’ (6).

But is this also true of the personalised coaching experience approach described here? Is it really all rainbows and unicorns for the alternative described here?

ASSESSMENT WITHOUT ASSESSMENT

This approach of closely integrating development and assessment involves minute-to-minute observations and judgements that are the basis of conversations. The conversations help to flag ‘what to do next’. Coaching capability is enhanced through this iterative approach. It is a kind of Assessment without Assessment where the focus is on learning and development.

The personalised approach allows the CD to cut some slack for different rates of learning. Provided the ‘must haves’ are covered, some variation in learning outcomes can be tolerated.

More than 50 years ago Lee Cronbach (7) defined assessment as a procedure for drawing inferences. It is easy to see how the process of observation > judgement > discussion fits this definition without the need for a summative assessment.

SUMMATIVE ASSESSMENT

A summative assessment takes place at the end of a learning period. It measures what the learner has learned. This may lead to a grade or be used to affirm mastery of the learning.

BRING PEOPLE ALONG WITH YOU

It is important to bring people along whenever change is proposed (See Dawn Ho’s post on change here). Coaches may initially be sceptical of a new or different approach. Administrators with a concern for risk management may be sceptical if the approach is different from what they know. Funding agencies and other peak organisations may also need convincing.

Time should be taken to explain how the approach may be different from other learning experiences coaches may have had. Coaches may expectations of being told what to do. This calls for some explanation of the how and why of more collaborative learning approaches.

Developing learn-to-learn skills may be the most important thing we can help coaches with.

WHAT ABOUT a HYBRID APPROACH?

A hybrid approach, mixing the personalised coaching experience approach with some endpoint (summative) assessment might act as a useful transition strategy for those wanting to dip a toe.

Even if your Sport’s assessment requirements are heavily weighted toward a summative assessment approach, the ideas outlined above which are based on trained personnel observing, supporting, and offering guidance through conversations, is still available to you. What are you waiting for?

Good luck! 😊

REFERENCES

- McCarthy, L., Vangrunderbeek, H., & Piggott, D. (2022). Principles of Good Assessment Practice in Coach Education: An Initial Proposal. International Sports Coaching Journal, (9)2, 252-262.

- McCarthy, Liam. (2025). Sport Coach Education, Development, and Assessment (International Perspectives). Routledge, New York, and London. (See chapters at: p1, 62, 75).

- InnerDrive blog. What is the Spacing Effect? Available here.

- InnerDrive blog. 10 Advantages and Disadvantages of Classroom Group Work. Available here.

- Grant, Adam. (2023). Hidden Potential (The Science of Achieving Greater Things). Penguin Random House UK.

In this highly readable book, Adam Grant writes about maximising group intelligence by bringing people together to solve a problem. The smartest teams are not the ones with biggest IQs, but the ones with pro-social qualities enabling them to effectively collaborate. (See pp. 179,181, 188, 198) - Collins, D., Burke, V., Martindale, A & Cruickshank, A. (2014). The Illusion of Competency Versus the Desirability of Expertise: Seeking a Common Standard for Support Professions in Sport. Sports Medicine, 45(1). The article is available here.

- Cronbach, L.J., (1971). ‘Test Validation’ in Thorndike, R.L. (ed.) Educational Measurement. 2nd. Edn. Washington DC: American Council on Education, pp. 443-507.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Lawrie Woodman for providing useful feedback.