Liam McCarthy, PhD.

Rethinking Coach Development: Inquiry and the Power of Assessment

Coach development is often described as programs, qualifications and competencies. Liam McCarthy sees it differently. For him, it is about inquiry, experience, reflection — and rethinking how we use assessment.

In this wide-ranging conversation, Liam reflects on how he entered the field, what he has learned working with national sporting organisations around the world, and why assessment may be the most underused lever in coach learning.

Liam is a Reader in Sport Coaching in the Carnegie School of Sport at Leeds Beckett University. He has observed that assessment which is in the forefront of coaches’ minds when they undertake a course has been little studied by researchers and underappreciated for its potential contribution to learning. His mission has been to change all that.

The International Council for Coaching Excellence (ICCE) engaged Liam to provide fresh thinking about how coach developers might best use assessment. He has also edited the go-to book on assessment in coach education and development.

Excellent examples of the integration of inquiry approaches to learning, project-based learning and assessment embedded into the learning experiences, can be seen in work Liam has done with the Premier League, and Swim England. These programmes are at the cutting edge of coach learning and development.

In his spare time, Liam runs marathons (for fun!) and enjoys family life watching his young daughter grow.

An Accidental Entry into Coach Development

“I didn’t set out to become a coach developer,” Liam admits.

He graduated around the time London was awarded the 2012 Olympic Games. In the decade leading up to the Games, significant investment flowed into minority sports in the UK, including handball and volleyball. With host-nation participation guaranteed, these sports needed infrastructure — particularly coaching infrastructure.

Handball advertised for a “Head of Coaching.” The title sounded grander than the salary, but Liam applied. He had a sports science and management degree, experience coaching soccer, and a broad understanding of sport. That was enough.

The role was ambitious: build courses, create pathways, and support a workforce of coaches ranging from school leaders and teachers to community volunteers and performance coaches. Many had little formal support in a sport that was under-resourced and relatively unknown in the UK.

“I stepped into the role and figured it out,” he says. “That was my entry into coach development — a world I didn’t even know existed.” He spent five years in the role.

The bridge from research to practice

While working in handball, Liam began a part-time Master’s degree to help him navigate the challenges he was encountering. That led to self-funded doctoral research and, eventually, a university career.

Academic roles in the UK typically involve three elements:

- Teaching

- Research

- Knowledge exchange (working with industry partners)

It was this third element that resonated most strongly.

“Because I’d worked in an NGB, I felt drawn to helping people like my former self solve real problems,” he explains. Liam is a strong advocate for using research findings to benefit practice.

Over time, knowledge exchange became his primary focus. He now collaborates with a range of organisations including the English FA, the Premier League, US Soccer, UEFA, FIFA, Swim England, World Athletics, the European Handball Federation, Netball and US Tennis.

Despite differences in sport and geography, he sees recurring patterns. “It’s amazing how common the problems are.”

Building Connections the Simple Way

There was no master networking plan. He didn’t set out to be very strategic or to build a network. It was almost accidental.

“I just put myself in rooms with practitioners,” he says. “I asked questions. I listened. I tried to understand their challenges.”

One recurring theme across organisations was assessment. Everyone knew assessment was necessary. Few were confident it was being done well.

That shared concern eventually led to collaborative projects, including a book bringing together perspectives from across sports and countries. “That felt like a really important moment,” he says.

What Makes the Work Meaningful?

For Liam, the highlight is simple: the people.

Sport does not always offer strong financial rewards or ideal working conditions. Many coaches and coach developers stay in the sector because they care deeply about the impact they can have. There is a mismatch between how coaches are remunerated and the huge contribution they make.

“Every Olympian started as a young person in a local club,” he says. “If we want better outcomes at the top, we need better experiences at the beginning.”

That commitment to improving experiences for children and athletes continues to motivate his work.

A Coach Development Philosophy

Liam resists fixed labels, but several principles guide his continually evolving thinking.

First, coaching is complex. It is shaped by context, relationships, culture and politics. It is rarely routine. Because of this, simply delivering solutions (to unknown or at best, poorly formed problems) is insufficient. We have to start by understanding the coaches’ world, who they are and what their job entails. And then if we are lucky enough, we can seek to influence things they do with questions and ideas.

“If coaching is unpredictable and contextual, we can’t start by handing out answers.”

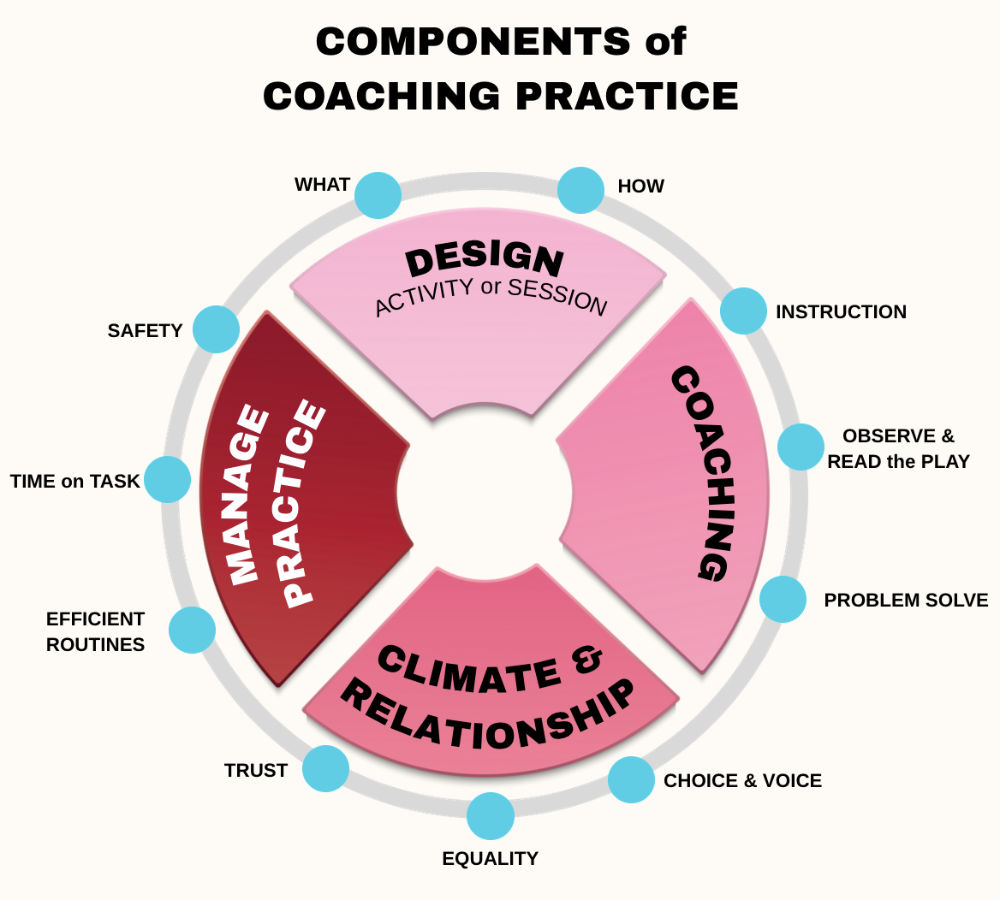

Instead, he believes coach development should focus on three interconnected elements:

- Experience – Coaches learn by doing.

- Sense-making – They reflect on those experiences, individually and with others.

- Insight – New understanding emerges through that process.

Too often, insight is treated as something delivered externally — by course leaders, gurus, academics or policy documents. Yet coaches generate valuable practical knowledge daily.

“We don’t value coaches’ practical knowledge nearly enough.”

Coach development, in his view, should begin by understanding coaches’ realities before introducing new ideas. “What we can’t do is just give them lots of solutions, because we don’t know what the questions are yet,” he emphasises.

Coaching as Inquiry

Liam has long been interested in inquiry-based learning — the idea that education begins with questions rather than answers.

Recently, through work with colleagues in aquatics, he has revisited some of the foundational texts in this area.

“I think coaching is informed guesswork,” he says. “If we start there, it disarms everyone. We’re all experimenting. We’re trying things and adjusting.”

This mindset shifts the emphasis from being right to being curious. Coaching becomes a process of ongoing and gradually more informed experimentation.

The best coaches, he argues, are committed learners. They ask good questions. They are comfortable not knowing.

Assessment: The Untapped Lever

Assessment has been central to Liam’s thinking for nearly two decades. His work with Handball was the genesis of his thinking about assessment.

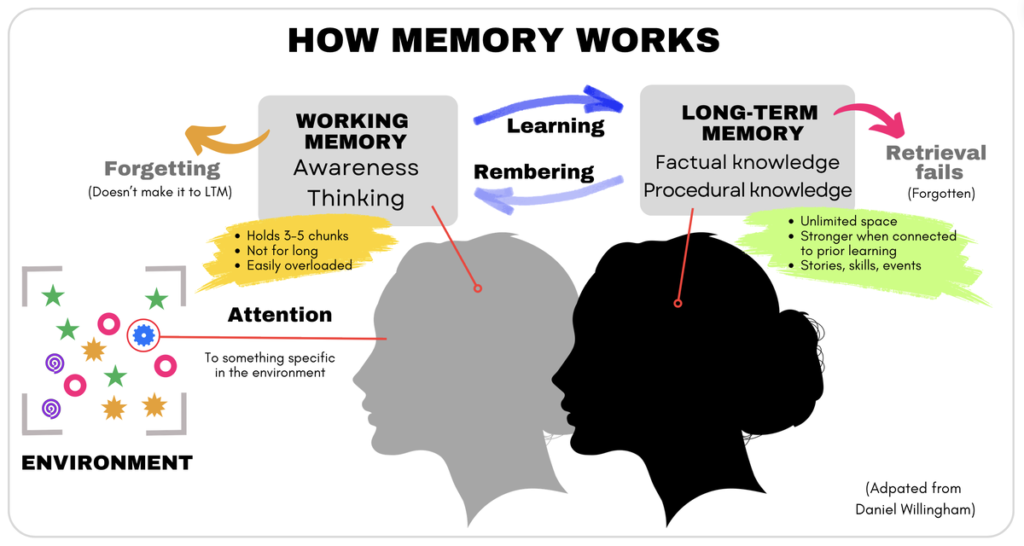

Early in his career, he developed rich learning experiences for coaches — communities of practice, field-based learning, reflective activities. Yet assessment remained largely unchanged: a final, high-pressure practical test at the end of a course.

“It felt disconnected from learning,” he recalls.

Over time, he began asking a simple but provocative question:

Why spend precious course time doing something that undermines learning?

Assessment became the focus of Liam’s PhD. Through work with organisations such as the English FA and the Premier League, he began exploring alternatives — including project-based assessment, longer-term inquiry tasks, and building evidence of learning over time.

He has become increasingly convinced that assessment and learning should be inseparable. Rather than subtract from valuable learning time, assessment should enhance learning outcomes.

Rather than distinct “assessment moments,” coach development programmes can:

- Integrate feedback continuously

- Use real-world projects as evidence

- Build a longitudinal picture of progress

- Treat learning activities themselves as assessment

The aim is not to eliminate rigour but to align assessment with the purpose of learning.

“Make assessment a powerful learning experience.”

Just treat the learning activities as the assessment activities and start to build a view of the coaches’ progress over time without any designated assessment moment.

“This approach will give us the biggest opportunity in the future to improve things,” he says.

A Highlight: Project-Led Learning in the Premier League

One of Liam’s proudest achievements has been redesigning the Premier League’s coach development programs. Work he has done over the last seven years.

These programmes serve professional, full-time coaches working in high-performance football clubs. Rather than traditional coursework and testing, the new model centres on two-year, project-led inquiry.

Coaches investigate real challenges in their environments and produce tangible outcomes — policy documents, curriculum redesigns, staff development initiatives, new resources.

Over 130 coaches have completed the programme. It is typically work-based learning because the coaches are working full-time, six days a week.

“They’re changing football through the work they’re doing,” Liam says.

Importantly, these projects serve as assessment — but coaches rarely experience them as such. They are embedded in meaningful work.

At a celebration event, one coach told him:

“I’m always going to frame my practice through projects now.”

That shift — from completing requirements to leading inquiry — is, for Liam, transformative. Reinforcing the message, he says, “I don’t think you ever get there by commanding people to write essays or telling people they need to write a reflective diary.”

The programme has also received academic recognition, including an International Sport Coaching Journal award, demonstrating that rigorous scholarship and meaningful practice can coexist.

Assessment Challenges

Despite promising developments, significant barriers remain.

Cultural Expectations

Globally, assessment is often associated with measurement, judgment and box-ticking. Shifting those deeply ingrained assumptions is difficult.

Legal and Risk Concerns

In some contexts, particularly in the United States, organisations fear that without clear summative assessment moments they may be legally vulnerable.

“It’s really hard to persuade individuals and organisations to break free of traditional assessments because the practices are just so embedded. So, we’re almost ensuring and committing legally to the less safe option. It just sounds bizarre to me,” he remarks.

Liam finds this paradoxical. A one-off competence check does not guarantee safe or expert practice. In some cases, a more sustained, learning-oriented approach may better support safety and quality.

Investing in Coaches

Perhaps most challenging is the financial structure of coach education. Liam gets quite passionate thinking about just how many more crises it will take for us to start investing in coaches rather than trying to profit from coaches.

Coach education is frequently treated as a revenue stream rather than a strategic investment. Coaches — often volunteers — pay substantial fees for qualifications.

“We should be investing millions in coaches and expecting nothing back in financial terms,” Liam argues. “Coaches are so central to sport.”

Without strong coaching, athlete welfare, retention and performance all suffer.

Preparing Novice Coaches

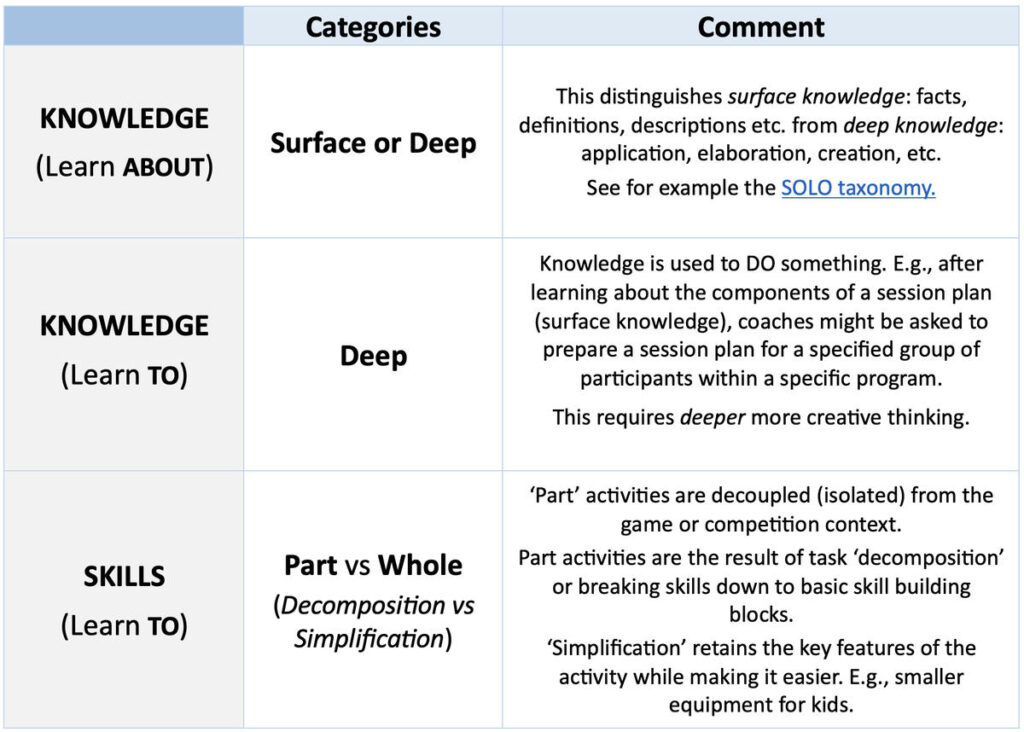

In many countries, 80–90% of registered coaches are beginners or volunteers. They often coach for a short period, frequently linked to their children’s involvement.

These coaches need confidence and clarity early on. Some structured, direct instruction may help — just as beginner players benefit from simple, reduced-complexity practice.

But Liam cautions against staying in that mode too long. When athletes are sufficiently confident with fundamental skills, new challenges should be added. So it should be with coaches. Introduce challenge at the earliest possible opportunity.

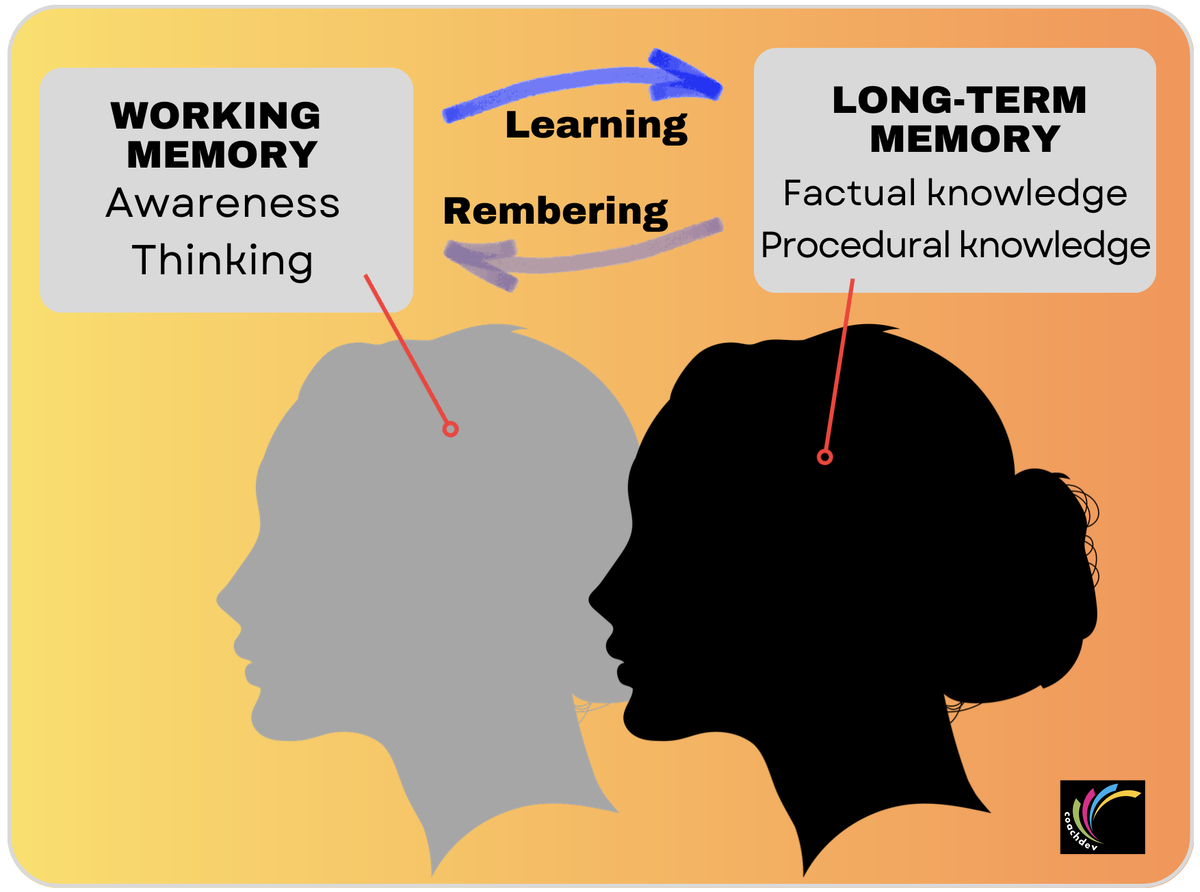

If coaches only experience passive learning environments — sitting, listening and accepting ideas uncritically — they may replicate that approach in their own coaching.

“If we want thoughtful, reflective coaches, we need to model that in their development.”

Taking Coach Development to the Next Level

When asked what needs to change, Liam returns to three themes:

- Rethink assessment – Integrate it with learning rather than separating it. “Assessment is probably the biggest untapped lever we have.” Pull quote

- Invest properly in coaches – Recognise their central role in athlete wellbeing and sport sustainability.

- Adopt inquiry-led, work-based models – Help coaches surface meaningful questions before offering solutions.

None of this is easy. Cultural expectations, funding models and institutional inertia are powerful forces. But he believes the opportunity for taking coach development to the next level is significant.

Liam’s recently helped Swim England completely reimagine how coaches are developed. This is a good example of the connection between the mental models that underpin coach development and how coaches go about their work following the course or developmental program.

“In my view if you have a coach education system where at each stage you are asking coaches to uncritically accept a set of predetermined ideas, then coaches will learn that’s what we do – not question or challenge anything. This then trickles down into how coaches support athletes – they have power, ideas about what is right, and the athlete should accept that. And this will all be at the expense of the athlete’s wellbeing.”

Mentorship and Learning from Others

We asked Liam if he had a mentor?

“Probably many,” he says. “None of these ideas are mine alone.”

His thinking has emerged through collaboration, travel, observation and dialogue. If mentorship means learning from others, then it has been a constant — though rarely formal.

He also recognises that the language of mentoring can create hierarchy. In many ways, his approach is consistent: learning is shared, relational and ongoing.

Final Reflections

Liam’s work challenges several deeply embedded mindsets in coach development:

- Deliver content first.

- Test it at the end.

- Expect the unproblematic adoption and implementation of ideas in practice.

Instead he advocates:

- Starting with coaches’ questions, as they notice and frame them.

- Recognise there is always novelty at the point of delivery (coaching).

- Valuing practical knowledge that emerges through coaching.

- Treating assessment as learning.

- Investing seriously in coaches.

- Embracing inquiry over certainty.

For coach developers, the implications are significant. If coaches shape athlete experience — and athlete experience shapes sport’s future — then the design of coach development is not a peripheral concern. It is central.

And perhaps the most powerful place to begin is with a question:

How can we make every part of coach development — especially assessment — a genuine learning experience?