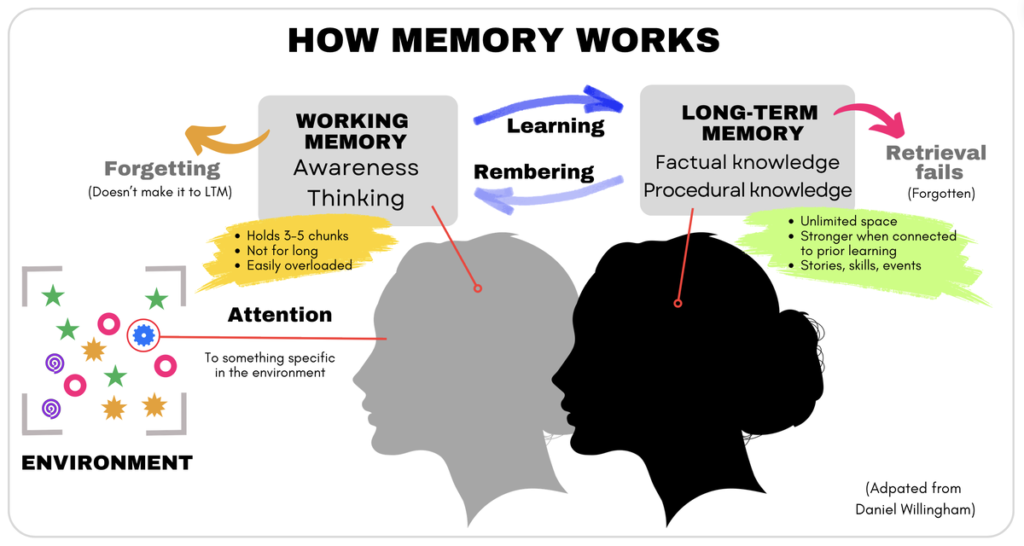

Learning takes place when information in our conscious thinking is transferred to long-term memory. Organising these memories, through a network of neural connections, builds our capacity to tackle novel and unpredictable situations.

These connections can be varied and may include visual, auditory, emotional, or kinaesthetic memories.

Understanding how our memories are formed helps us to understand the differences in performance between novices and experts. It also guides the coach and coach developer in designing instructional strategies. That is, how to be a more effective teacher.

My brain is full!

In a favourite Gary Larson cartoon, teacher Mr Osborne at the front of his class glances over his left shoulder. A student has his hand up. The student asks: “Mr Osborne, may I be excused? My brain is full.” You can see the cartoon by here.

Apart from being pretty funny, this cartoon is a good catalyst for a discussion about how CDs and coaches can effectively get the message across. It also invites us to challenge simplistic notions that teaching is just about transmitting information with the hope that is sticks. Telling is not teaching.

(BTW, telling is not the same as explicit instruction. But that is another article).

What are you thinking right now?

Back to the cartoon. The student’s long-term memory (LTM) has plenty of unused capacity. No problem there. The problem is most likely an overloaded working memory (WM).

Working memory is whatever is held in your consciousness at any given moment. Understanding working memory is the key to learning.

Working memory

This is your memory for the present moment. It is a limited and short-lived holding space in your prefrontal cortex for the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, emotions, and language of right now - working to keep whatever you just experienced and paid attention to only long enough to use it or not.

Lisa Genova, p38.

Pay attention!

When attention is narrowly focussed thinking is unlikely to be overwhelmed by extraneous things in the environment. (See the diagram below).

When too many distractions not relevant to the immediate learning are present, cognitive overload occurs. Too much mental effort is required to make sense of things. Working memory is ‘stretched’ beyond its limits – it becomes overloaded.

To learn something, we have to notice things. Noticing requires us to do something with all the sensory information the brain receives. This requires paying attention. That is, fine tuning our thinking to actively process specific information in the environment while ignoring other sensory input.

Apart from unimportant things in the environment, there is lots going on in our heads to ignore: self-talk, reliving conversations, to-do lists, random thoughts … the monkey mind.

The brain can receive and process sensory information, like watching an athlete perform a skill BUT unless there is a deliberate and focussed attention to what is being perceived “the activated neurons will not be linked, and memory will not be formed.” (1, p27).

“PAY ATTENTION!”. The command is a futile one unless the learner is receptive to whatever attention is being drawn to.

We are attentive to things that are meaningful and interesting. Something that is surprising, humorous or resonates with us emotionally will grab our attention and open the gate to learning.

Our brain’s default setting is not to be attentive. We have to work at it. This means the CD or coach needs to create an environment favourable to learning and to choose learning experiences that are interesting and meaningful to the learner.

Mr OSBORNE’S CLASS. So, even if Mr Osborne’s teaching practice is good, his student with a ‘full brain’ may have no interest in the topic and no interest in paying attention.

We have to know stuff to learn

“New knowledge can only be understood if it is linked to what the student already knows.”

Mike Bell

The more links the better. Using multiple senses (multi-sensory) and emotions makes the memories easier to recall and less likely to be forgotten.

When prior knowledge is retrieved, more than a single piece of information is accessed.

Information in the brain is not stored in an isolated manner, like a piece of information on a computer hard drive. It is stored along with other information and emotions from all the senses. A memory is a network of connections.

Back to Mr Osborne's class

Back to our student in Mr Osborne’s class. Numerous things could be interfering with the student’s ability to process what he is seeing and hearing from Mr Osborne.

A run-in with a peer may have led to our student dwelling on an earlier incident. The student may be dealing with something from home. Perhaps he didn’t complete his pre-class work. Essential prior knowledge may be absent. Or Mr Osborne, may be overwhelming the class with too much information and at the wrong level. Or maybe the class just needs a short brain break and the student with his hand up is expressing what others are feeling.

The student’s WM is working overtime, and nothing is making sense. Extraneous thoughts, some possibly emotionally charged, compete for WM space. We have all been there!

Coaching young participants

The example of Mr Osborne’s class is not uncommon in our everyday coaching.

We have all experienced working with young participants where one or more of them come to training frazzled. It may take us 10 or more minutes into our ‘perfect’ session plan before we realise things are not going to plan. Our strategies for getting participants to focus on what matters may be good.

But something in the lead up to training has emotionally charged one or more participants.

What we might want participants to hold in WM clashes with what is already there. ‘Reading the play’ and adapting is a key coaching skill. In our example, the change to the plan may have to be significant.

CD & Coach Take-outs

Here are some strategies adapted from Mike Bell (2):

- Develop session routines and habits. For CDs teaching or coaches working with athletes, routines should be taught and practised to avoid wasting time and clogging up WM.

- Convey information in smaller chunks.

- Connect new information to prior knowledge by linking instructions and new information to things that are already part of the learner’s existing knowledge or everyday experience.

COACHES

- Coaches should keep cues simple and short (KISS – keep it simple and short)

- Use similes and analogies to help participants connect more complex ideas with things that are familiar in everyday life.

- Arrange equipment and the playing / training area in ways that reduces the amount of cognitive processing that is required (constraints-based approach). This may reduce the need for verbal instruction or eliminate it altogether.

COACH DEVELOPERS

- Use multi-sensory strategies (also relevant to coaching)

- Focus attention with content that is interesting, meaningful, surprising, humorous or tugs at our emotional heart strings

- Use active learning strategies (this will call on different sensory strategies such as talking with peers and physically moving – these have the potential to reduce cognitive load)

- Link abstract ideas to concrete analogies.

FIG. HOW MEMORY WORKS

In this final figure more detail has been added. Procedural knowledge enables us to type, tie our shoe laces or execute a skill or activity in sport. Memory is not just about ‘book learning’ – it is also at the centre of doing things physically.

References

- Genova, Lisa, (2021). Remember. The Science of Memory and the Art of Forgetting. Simon Schuster.

- Bell, Mike. (2021). The Fundamentals of Teaching. Routledge.

By Gene Schembri

By Gene Schembri

By Brett Reid

By Brett Reid